|

A

summary of the paper presented to 5th Congress of the International Association of

Semiotic Studies,

The Division of Signs: Dave Hiles (Email: drhiles@dmu.ac.uk )

ABSTRACT: This paper proposes that two completely distinct sign functions underlie the symbol. Using Roman Jakobson's two fundamental dimensions of sign function: Factual/Imputed and Similarity/Contiguity, two types or functions are proposed: (1) The Artifice - imputed/contiguity - entails a sign function involving arbitrary relation between signifier and signified which arises from systemic division of the whole into parts; (2) The Motif - imputed/similarity - entails a sign function with a motivated relation between signifier and signified which arises from some shared quality between them. These qualities do not entail physical resemblance, but are ascribed or imputed often unconsciously. The distinction between motif and artifice addresses directly many of the problems in the discussion of the nature of sign and sign function. It is argued that the distinction overcomes frustrations in the application of semiotics to other fields, particularly psychology.

The statue of Anubis,

found in Tutankhamun's tomb, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, has one very

curious feature (Figure 1). Anubis, the jackal god of death, guardian

of the gates to the underworld, and keeper of souls, has a human eye.

One interpretation offered by Egyptologists is that this indicates that the

ancient Egyptians understood clearly the nature of the sign function

that lies behind the symbols of their culture. Portraying an animistic symbol

with a human eye emphasizes how the jackal image evokes particular qualities

in the human mind.

The jackal symbol

functions as a material object which has the power to awaken deeper

understanding, or unconscious knowledge, in the beholder. The jackal is an

animal that buries the flesh of its prey, which it does not eat until

rotted. Anubis is therefore a symbol of digestion, and leads the soul of the

deceased through the "digestive" stages of mummification. The

Egyptians did not worship the jackal as a god, but recognized in it the

qualities that symbolize the journey which death will involve. Of course,

this type of symbol is commonplace and central to all cultures, from the

image of water in a painting or dream that can signify the unconscious, to

the ring on a finger that signifies fidelity, eternity. These cultural

symbols clearly are not purely conventional or arbitrary, and therefore

challenge current semiotic theory of signs. 1. Semiotics and psychology The unique power of symbols lies in their ability to reveal

levels of reality otherwise hidden, to open the human mind to wider awareness.

The psychologist Carl Jung has proposed that with so many things beyond the

range of human understanding "we constantly use symbolic terms to

represent concepts that we cannot define or fully comprehend" (Jung,

1964: 21). Clearly, any psychology that gives a central place to the study of

meaning and how it arises in human action and experience must recognize the

theoretical tools that semiotics can offer. Semiotics is both a theory of

knowledge and a theory of mind, i.e. SIGN = MIND. Nevertheless, the

application of semiotics to psychology and theories of the human mind is

frustrated by current notions of the nature of the symbol. 2. Symbols and the classification of signs The division of signs is fundamental to all semiotic science, and yet remains controversial. Sign typologies may be crude divisions of signs, but their importance lies in pointing to the different underlying sign functions linking signifier and signified. In Peirce's now familiar classification of signs, the division of signs into icon/index/symbol, is more or less based upon three underlying sign functions: similarity/contiguity/convention respectively (Peirce, 1902). This agrees with Saussure (1915 [1966]) who, concerned only with the linguistic sign as symbol, regarded the relationship between signifier and signified as arbitrary. Thus the principle of the symbol as an arbitrary/conventional sign became established. Such a principle, that regards the underlying sign function of the symbol as one of pure convention, certainly has difficulty in explaining the nature of cultural symbols. 2.1 Roman Jakobson's classification

of signs

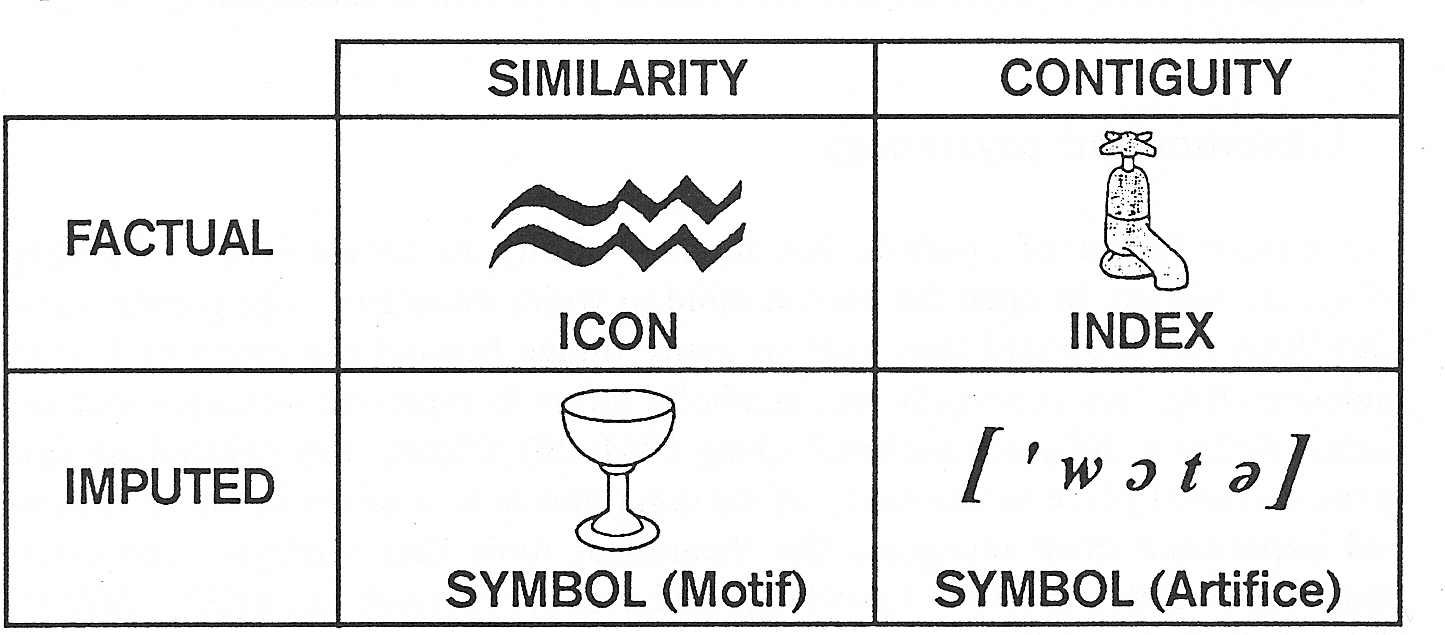

Figure 2: The proposed four-fold division of signs, using signs for "water" as illustration

2.2 The revised four-fold

classification

2.3 Artifice and Motif (i) The Artifice - imputed/contiguity - entails a sign function involving arbitrary relation between signifier and signified which arises from systemic division of the whole into subdivisions or parts. The linguistic sign is the example par excellence, but is by no means the only example, arbitrary division is a common cultural device. It is this type of sign which may be uniquely human, and enables the mind to extend its powers beyond immediate impression. (ii) The Motif - imputed/similarity - entails a sign

function with a motivated relation between signifier and signified which

arises from some shared quality between them. These qualities do not entail

physical resemblance, but are ascribed or imputed by conscious, unconscious,

collective or archetypal projection. The motif is at the same time both

universal and subject to socio-cultural convention. The dream symbol is the

example par excellence, while also fundamental to art, poetry, culture,

religion, and particularly to narrative (Hiles, 1996). 3. Some implications and conclusions This proposed four-fold division of signs, together with the distinction between motif and artifice, addresses directly many of the problems in the discussion of the nature of sign and sign function. The confused definition and debate on the nature of symbols is clarified. Peirce's typology is seen as incomplete. Saussure's work can be seen to be concerned exclusively with artifice. Post-Saussurian developments such as Structuralism are simply over-concerned with artifice at the expense of the motif. A quite new perspective is offered for such issues as sign motivation, reference/denotation and connotation. Furthermore, it is argued that popular typologies of sign in circulation serve to frustrate the application of semiotics in other important fields. The application of semiotics to cultural signifying practices is vacuous without the recognition of the importance of the motif. The diversity of semiotics (e.g. into psychological science) will be promoted by the recognition of the motif sign function. And, semiotics will have finally absorbed something that was all too obvious to the ancient Egyptians!

References Hiles, D.R. (1996) "Narrative as a sequence of motivated signs", in I. Rauch and G.F. Carr (eds), Semiotics Around the World: Synthesis in diversity. Proceedings of the Fifth Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies, Berkeley. June 12-18, 1994. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Jakobson, R. (1968 [1971]) "Language in relation to other communication systems." Selected Writings Vol II: Word and Language. The Hague: Mouton. Jakobson, R. (1980) The framework of language. Michigan Studies in the Humanities, Vol. 1. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Jung, C.G. (1964) "Approaching the unconscious", in C.G. Jung (Ed) Man and his symbols. London: Aldus Books. Peirce, C.S. (1902 [1931-1958]) Collected papers Vol. 2. Translated by C. Hawthorne and P. Weiss. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Saussure, F. de (1915 [1966]) Course in general linguistics. Translated by W. Baskin. New York: McGraw-Hill.

|

||