|

A

summary of the paper presented to 5th Congress of the International Association of

Semiotic Studies,

Narrative as a Sequence of Motivated Signs (Psychology, De Montfort University, Leicester. LE7 9SU. UK.) (Email: drhiles@dmu.ac.uk ) ABSTRACT: The nature of narrative is explored drawing upon interests in the theory of signs, the nature of the human mind, and the practice of psychotherapy. Narrative is universal to all human cultures, inseparable from and intrinsic to our social and cultural experience. In therapy (confirmed by case material), narratives often announce crucial moments of insight and integration giving voice to underlying conflicts and concerns, representing a struggle for order, structure and meaning. Human behaviour is multi-determined, narrative offers powerful ways to conceptualize the complexity of human action, ways that do not stress causality, but offer non-positivistic explanations, unique modes of understanding. Defining narrative is frustrated by the omission of the motif - a distinct type of unconsciously motivated symbol - from the theory of signs. Indeed, narrative is a universal expression of the motif - narrative is a sequence of motivated signs.

This paper recounts (as a story) a journey into the nature of narrative informed by theoretical and professional concerns with psychotherapy practice, the nature of the human mind, and the theory of signs. Narrative is a primary mode of thought. In psychotherapy, narrative offers powerful ways to conceptualize the complexity of human action. Examination of the story structure of therapy case material leads to the proposal that narrative is a universal expression of the motif, a distinct type of unconsciously motivated symbol, often overlooked in the theory of signs.

1. Beginnings The story behind this paper began several years ago. It arose out of my joint commitment to a theoretical interest in semiotics, the human mind, and the practice of counselling and psychotherapy. I was convinced that these areas were closely related. My clients, in their struggle for meaning, revealed the profound effect that talking, and being listened to, had on their personal growth and wellbeing. I became fascinated by the almost magical power of signs to make sense of human experience, and to facilitate integration of inner and outer realities. Armed with the insights of a cognitive psychology training, I remained dissatisfied with an overtly behavioural academic psychology, but also unconvinced by the fragmented world of psychodynamic and psychotherapeutic theories. Semiotics too, particularly the theory of signs, seemed to be lacking in the tools I searched for. My project for a semiotic psychology was faltering at the

first hurdle. Turning to linguistics, I was encouraged by discourse

analysis, but hardly nearer the goal of my quest. Then, help came strangely

from other fields similarly struggling to apply semiotic analysis to how

meaning is constructed, e.g. film theory. A recurring theme became the

importance of narrative in human communication. 2. A theoretical aside Narratives, whether verbal or visual, mediated or

face-to-face, constitute one of the most prevalent types of discourse.

Narrative is a fundamental characteristic of the human mind, a primary mode

of thought (Bruner, 1990). Signs when organised as narratives offer

fundamental cognitive structures. Thinking in a narrative mode has important

advantages over rational thinking (Polkinghorne, 1988), stressing that

reality and truth are always constructions, offering a sense-making process

that emphasises sharing with others, and providing an effortless,

unconscious and involving way of constructing our world. Consider the following reconstructed therapeutic case material (names, and some details have been changed). Narrative (N1.), 4 min. into Session 16:- Tom: [ . . ] We had another row. I (m)ucked things up this time. I hit her. [ . . ]

Ther.: [ . ] You lost your temper. You are sorry you hit her, pushed her over. Tom: Yes. [ . . ]

Mary is always saying I am not a man - she needs a man,

Ther.: Never enough. [ . . ]

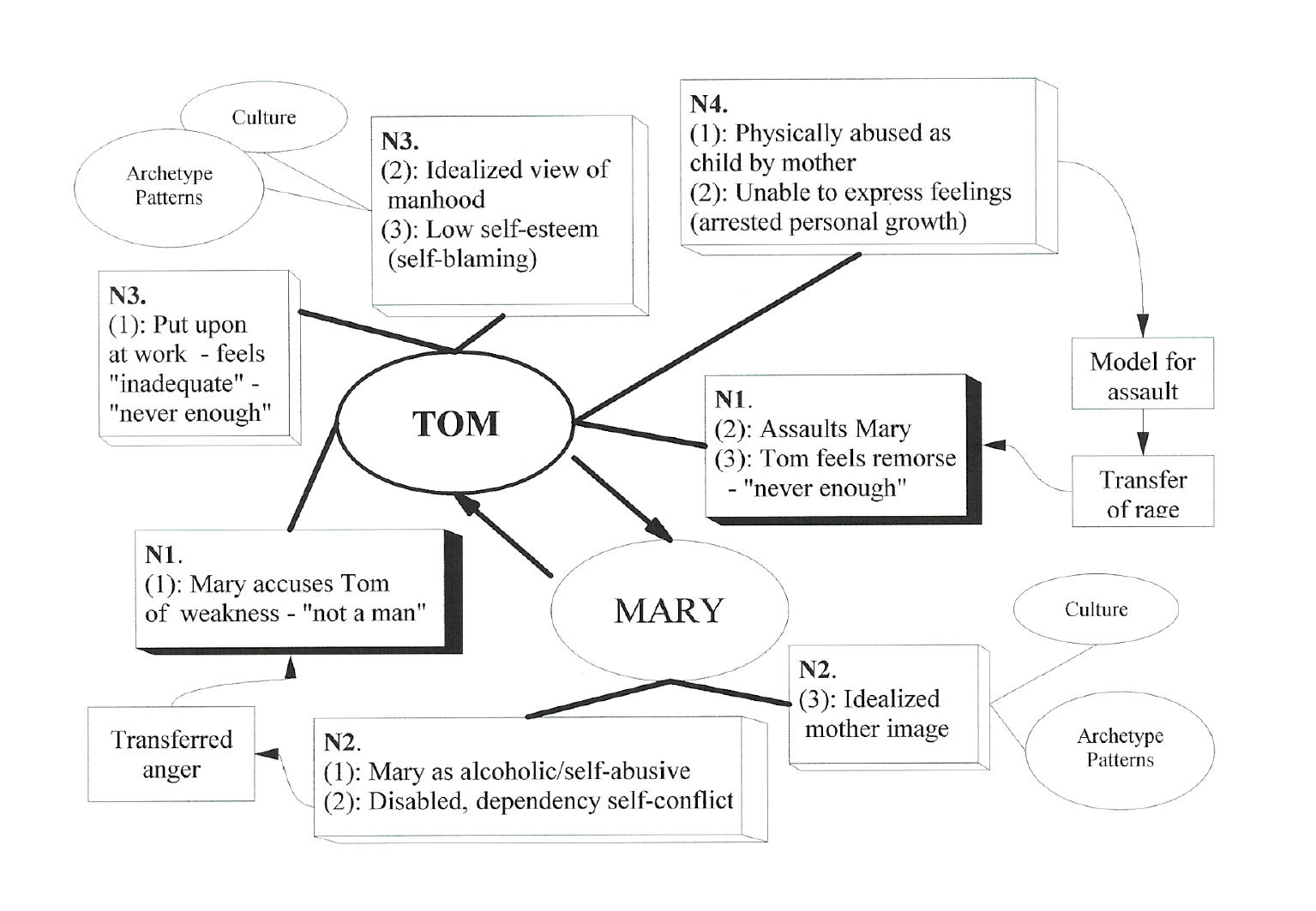

In therapy, the client intuitively falls into a narrative mode of communication. The therapist adopts a listening style of attention, which promotes the client's storytelling, and frequently leads to a free-floating chain of narratives. Such narratives often announce crucial moments of insight and integration. Examination of such case material illustrates several key points: (1) initiating a narrative involves a surface topic change, but often disguises an unconscious continuation; (2) discursively, narrative suspends turn-taking and resists interruption; (3) narrative gives voice to underlying conflicts and concerns, it can represent a struggle for order, structure and meaning; (4) therapeutic narratives often possess an unfinished quality, as one story follows on another. Figure 1 illustrates Tom chaining four narratives during Session 16. The story about the argument over the bill (N1.), is linked through stories about his wife's difficulties (N2.) and his work problems (N3.), to a story about a remembered incident when as a child he was physically abused by his own mother (N4.). The therapist's interventions consist of observations of unconsciously motivated anger; the realization that Tom's pushing Mary was similar to the way he was pushed by his mother; alongside awareness of the unconscious contribution of cultural norms and archetypal patterns to the story-meanings being explored. Nevertheless, it is clearly the client's skills of integration that are evident in the use of narrative. What emerges is that human behaviour is multi-determined.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of unfolding narratives in Tom's discourse

Narrative offers powerful ways to conceptualize the complexity of such human action, ways that do not stress causality by simple antecedents, but offer non-positivistic explanations, unique modes of understanding. Indeed, narrative is fundamental to human identity, our sense of self is constructed unconsciously in our life story.

2.2 Narrative and sign function A narrative is a sequence of signs. But it is not merely a sequence of signs, since, clearly there are sign sequences that are not structured as narrative. Inspection of Tom's discourse reveals unconscious motivation in the telling of the events. The events are related, not simply in the temporal order that the events occurred, but in an order determined by the conscious and unconscious significance of the events, as well as by the inherent organizing principles that narrative structure offers in the understanding of human action. Narratives are structured as a sequence of sign-events, where these events are signifiers of deep individual and universal psychological meanings. Such a view is supported by Propp (1928 [1968]) who analyzed a corpus of Russian folktales into a universal set of 31 functions (or motifs), and Lévi-Strauss (1969) who analyzed stories and myths into sets of binary oppositions, or bipolar contrasts, reminiscent of Carl Jung's archetypal structure of the unconscious. Hiles (1996) argues that there is a fourth type of

sign-function - the motif, which, with the exception of the work of Roman

Jakobson, has been overlooked in the theory of signs. The motif is a

distinct type of symbol, an unconsciously motivated sign, drawing on

universal, collective or archetypal meanings, expressing patterns of human

concern and importance. The motif is primarily a motivated cultural symbol,

it is central to artistic and personal expression, and is the fundamental

constituent of narrative. Exclusion of the motif from the theory of signs

raises serious difficulties in the semiotic analysis of narrative structure

and understanding the construction of personal meanings in stories. 3. Endings Resuming my story, it seemed clear to me that we dream, think, converse, write, entertain, illustrate, act, play, create self-identity, experience order and chaos, all in narrative. While the nature of narrative continually arose my interest, a working definition of narrative eluded me. For sometime I had been convinced that a sign function I had called the motif was being omitted from the theory of signs. The motif was a distinct type of symbol, an unconsciously motivated sign, drawing on universal, collective or archetypal meanings, expressing patterns of human concern and importance. This resonated precisely with Vladimir Propp's analysis of narrative structure. Indeed, narrative is possibly a universal expression of the motif. Put simply, it dawned on me that narrative is a sequence of motivated signs.

References Bruner, J. (1990) Acts of meaning. Cambridge: Mass.: Harvard University Press. Hiles, D.R. (1996) "The division of signs: A four-fold symmetry", in I. Rauch and G.F. Carr (eds), Semiotics around the world: Synthesis in diversity. Proceedings of the Fifth Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies, Berkeley. June 12-18, 1994. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Lévi-Strauss, C. (1969) The raw and the cooked. London: Cape. Polkinghorne, D.E. (1988) Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press. Propp, V. (1968 [1928]) Morphology of the folktale. Austin: University of Texas Press.

|

|