A

summary of the paper presented to the 18th International Human Science

Research Conference, Sheffield, UK, July 26 - 29, 1999.

© Dave Hiles 1999

Paradigms Lost - Paradigms Regained

Dave Hiles

(Email: drhiles@dmu.ac.uk )

ABSTRACT: The widely held distinction between quantitative and qualitative research is over-simplistic and quite misguided. It is important to note that what defines human science is not its methodology but its paradigms, and in a discipline such as psychology there is a real danger of losing sight of one’s paradigms. Guba & Lincoln (1994) define the term paradigm as "a set of basic beliefs that deals with ultimates or first principles [ . . that] are not open to proof in any conventional sense." All scientific research, indeed all human knowledge, follows a set of procedures that must begin with a group of assumptions, a set of beliefs, a paradigm. However, once a paradigm for research has been chosen, it is by no means settled what strategies and types of data collection and analysis are to be employed. All too often, research studies are criticized for their methodology without any consideration of the paradigm within which they fall. Students too are being taught qualitative methods, when really they are being taught only qualitative data analysis. In order to highlight and also resolve this confusion, a framework is proposed that makes a clear distinction between paradigm, strategy, methodology and (data) analysis, for all social, behavioural and human science research.

(1) INTRODUCTION

The debate concerning the growing acceptance of qualitative research in psychology is certainly a most welcome development. Nevertheless, there are some psychologists who view this development as quite controversial, and for many others it represents a departure from established practices of psychological research to be condemned at every opportunity.

There will be some psychologists who have adopted a qualitative approach, and together with many scientists in other branches of the social sciences, who can be forgiven for wondering "What controversy, what debate?" Hasn’t qualitative research, which is now widely used in the social and human sciences, been more or less accepted into psychology? Well, as recently as last October, in The Psychologist (the journal of the British Psychological Society), Professor Michael Morgan was arguing that qualitative research was presenting a serious danger to psychology (Morgan, 1998).

It is difficult to find fault with Morgan’s point that " . . what scientists are supposed to do is to collect novel and interesting data, which other scientists can rely upon" (p. 482). But there may be more than a little difficulty in everyone agreeing on exactly what is novel, and interesting, and there is considerable doubt that we could ever see eye-to-eye on what can be "relied" upon.

Morgan maintains that qualitative research constitutes one of several " . . determined challenges to the status of psychology as a laboratory-based subject" (p.481). He suggests that qualitative psychologists " . . pose a threat to traditional notions of psychology as a science" (p.488). And, furthermore, he is concerned that if psychology" . . goes down the road which qualitative researchers would like to follow" (p. 481), then this may contribute to the worrying trend that " . . psychology at university level is becoming an overwhelmingly ‘female’ subject" that will be "less attractive to ‘boys’" (p. 481).

It is perhaps too easy to dismiss Morgan’s argument as biased, ill-informed, or just not even worthy of serious attention. Nevertheless, his presentation of the issues does serve usefully to illustrate precisely what are the sources of confusion that persist in the current debate. For example, Morgan’s repeated use of the terms, qualitative psychology and qualitative psychologist, only serve to reinforce the simplistic comparison between qualitative vs. quantitative methods, the implication being that there is an all-or-none choice between qualitative and quantitative research. The idea that psychology can either "go down this road" or "that road" is naive. Morgan also stresses the importance of objectivity and reliability in research, yet he carefully ignores the more serious issue of the validity - an issue that equally concerns both quantitative and qualitative research, but which is a particular source of embarrassment to quantitative research. Another implication requiring serious challenge is the doctrine that what defines psychology is its methods, specifically its quantitative methods. Morgan seems to have no room for new methods, no place for examining and challenging the assumptions of the established methods, since these methods are well worked out. This is scientism at its very worst. This is bad psychology. This is bad science. This is so bad, it is sad.

This paper proposes that the issue that lies at the root of the confusion in this debate, and which is obscuring progress, is the continued focus upon the claim of a clear distinction between quantitative and qualitative methodology. It is a claim that is little more than a misguided attempt to polarize positions in the debate. Moreover, it is an issue that is an obvious symptom of the need for a more general model of the research process in scientific inquiry.

(2) QUALITATIVE METHODS – WHERE NEXT?

Psychology seems to be in a continual process of re-inventing itself. Echoes of the current debate between quantitative and more interpretative approaches to research are evident over a century ago in the work of Wilhelm Wundt and Wilhelm Dilthey. It was seriously addressed again, some fifty or so years ago, in the work of Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers and Rollo May. Most recently, in the movement to ‘rethink’ psychology, Smith, Harré & Van Langenhove (1995a; 1995b) have been arguing much the same thing. Again and again psychology, returns to confront the real danger of forgetting that what defines the field of psychology is not how we study, but what we study.

A qualitative approach to research typically makes a radical departure from the hypothetico-deductive method, and involves a more open-minded and exploratory strategy of inquiry. Data is gathered using interviewing together with phenomenological and heuristic accounts, and is analysed in the form of descriptions and meanings. As Giorgi (1985) remarks: "on the surface, it would seem that the acceptance of descriptions as raw data would have to exclude a scientific analysis" (p. vii). And yet, that is precisely what is being proposed.

Much of the resistance to a general acceptance of qualitative research stems from the idea that what defines "science" is its method. Science is method (cf. Lally, 1998), which some scientists take to mean: just one method - the experimental/quantitative method. The danger here is in forgetting that, first and foremost, the goal of science is an addition to knowledge, and not the method itself. It is a form of inquiry that is rigorous and systematic, and as such it is best conceived as a disciplined inquiry. There is clearly a place for qualitative research in disciplined inquiry.

Some qualitative approaches to research:

|

Another source of resistance that faces qualitative research is evident from a brief inspection of several textbooks that form part of a sudden explosion of publications in this area (e.g. Denzin & Lincoln, 1994; Banister, et al, 1994; Breakwell, et al, 1995; Richardson, 1996; Hayes, 1997). The first impression is of the confusing proliferation of methods that the qualitative approach throws up (see Table 1). Closer inspection reveals a much more serious set of issues: (i) a confusion between methods of data collection and methods of data analysis, (ii) a confusion between research strategy and research design, and (iii) little concern with the way theoretical perspectives can play a crucial role in research. It also seems fairly clear that students may think they are being taught qualitative methods, when really they are being taught only qualitative data analysis.

At a conference such as this, which is considering "Qualitative methods – where next?" it is worth reminding ourselves that what defines a human science approach to psychology is not its methodology, but its paradigm (cf. Giorgi, 1970; Polkinghorne, 1982), and all too often psychology is in real danger of losing sight of its paradigms.

(3) HUMAN SCIENCE AND METHODOLOGY

Considering my own perspective, I take the view that human behaviour is complex. We respond not to events, but to the meaning of events. Explanation of human behaviour requires more than simple causal, deterministic mechanisms. Human behaviour and experience are the consequence of multi-determined factors. We are historically, culturally and socially embedded. There is a place in research for interpretative analysis, co-operative inquiry, phenomenological and transpersonal methods. The areas of psychology in which I am interested raise concerns with respect to the understanding and description of lived-experiences. I may well need to use exploratory approaches, post hoc analysis, and attention to ecological validity, in my attempt to characterize the breadth, detail and rich contextuality of human events. The point is to choose research methods that fit with this perspective.

Guba & Lincoln (1994) have pointed out the importance of identifying the paradigm within which research is conceived and carried out. All human knowledge, all scientific research, follows a set of procedures that must begin with a group of assumptions, a set of beliefs, a paradigm. And yet, research studies, indeed whole fields of research, are frequently criticized for their methodology without any consideration of the paradigm within which they fall. In order to highlight and also resolve this confusion, the rejection of the conventional model of research is proposed. In its place a framework for disciplined inquiry is offered that makes a clear distinction between paradigm, strategy, methodology and (data) analysis, for all social, behavioural and human science research.

(4) THE CONVENTIONAL MODEL

The contention is that many of the confusions and problems that qualitative research faces, arise in the widely upheld quantitative/qualitative distinction. The conventional model of two distinct approaches to research is illustrated in Figure 1. The implication is that science, as disciplined inquiry, can be divided into two basic ways of approaching research which are more or less mutually exclusive. The point is that this basic model is not helpful, and needs to be rejected.

Figure 1: The conventional model of research

Quantitative research in psychology usually involves an experimental approach, that involves testing a hypothesis, and data collection that relies upon measurement and statistical techniques for analysis. Such methods have a well proven track record in all scientific disciplines, and not least in psychology. However, the limitations are also all too obvious. Measurement is basically a means of categorizing observations into a form suitable for mathematical manipulation. Such procedures always involve information loss and reduction. Establishing the reliability of measurements is reasonably straightforward, but the use of numerical data is no guarantee of validity whatsoever. Quantitative research design stresses manipulation, control, and causal/deterministic reasoning, and for some areas of study these may be either inappropriate, or unethical. Clearly, there is a wide range of human phenomena that may be very difficult to measure, so psychologists simply end up studying what it is easy to study. Often what is most interesting about people cannot be measured. The simpler issues are examined at the expense of the more complex. Important areas of research are deferred. Typically, measurements are devised to suit some apriori hypothesis, while other possible measurements and data collection are completely overlooked.

Qualitative research differs from experimental/quantitative research in several key respects. There is a deliberate attempt to collect data in the form of descriptions and meanings, especially in a way that is phenomenologically sensitive, honouring the experiential component of all knowledge, participation and observation. Qualitative research often utilizes triangulation (Janesick, 1994), and the concepts of validity and reliability need to be replaced with: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (Robson, 1993). Researcher bias can be a problem, but it is dealt with by being brought out into the open and acknowledged. Research is recognized as involving co-operative inquiry (Reason, 1988, 1994; Heron, 1996), in which data observations are not collected on human subjects, but with human co-researchers. A grounded theory approach may be adopted, in which theory follows data collection rather than theory driving data collection through hypothesis and prediction (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

What is less obvious is that there is nothing to rule out using both quantitative and qualitative approaches within the same study, and that the comparison involves more than differences in methodology. It does not take too much reflection to realize that much of the discussion on research methodology in psychology is quite muddled, and this is largely due to the failure to make a very practical distinction between the necessary basic components of any research activity. These are outlined in the discussion of a revised model of disciplined inquiry below.

(5) A REVISED MODEL OF DISCIPLINED INQUIRY

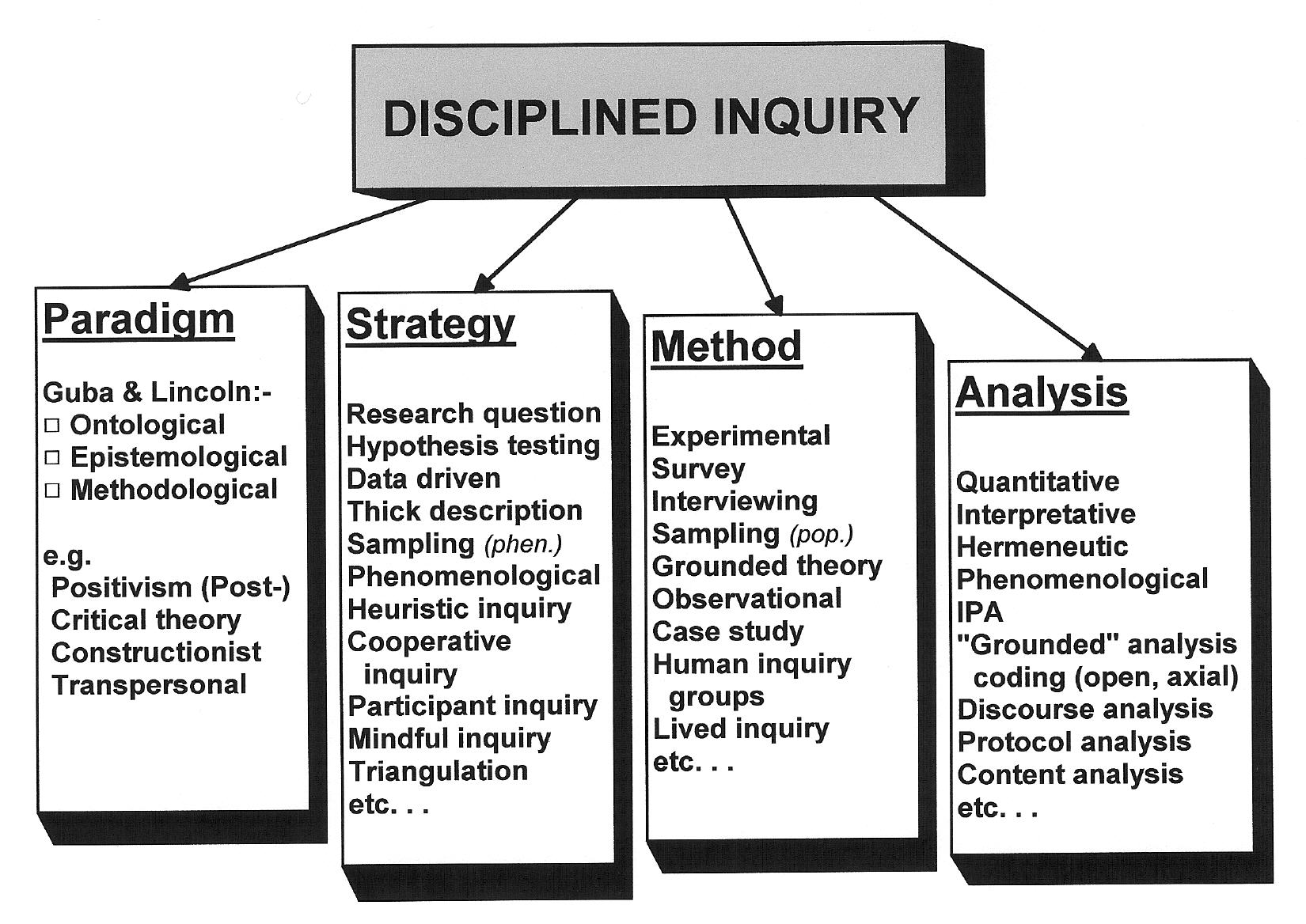

Disciplined inquiry is defined as a systematic and reflective pursuit of knowledge. It clearly embraces a very wide variety of approaches to scientific research, that can be organized by their assumptions, choices, procedures and analytical techniques. The model is presented in Figure 2. There is very little here that is new, except perhaps the emphasis and overall vision.

The model offers a distinction between these four aspects of the research process:-

- paradigms (assumptions adopted towards truth, reality, knowledge, and

- strategies (choices with respect to how disciplined inquiry is to proceed)

- methods (procedures for the collection of data)

- analysis (techniques for the analysis of data).

how knowledge is to be used)

There is no explicit distinction in this model between quantitative and qualitative research. Both are included and organized appropriately under each aspect.

Figure 2: A model of disciplined inquiry

The approach outlined here follows on mainly from the important work of Guba & Lincoln (1994), but considerably extends it. Guba & Lincoln stress the importance of recognising the paradigms at work in the natural, social and human sciences. They suggest that " . . a paradigm may be viewed as a set of basic beliefs [or assumptions] that deals with ultimates or first principles" (p. 107). They emphasize that a paradigm is " . . not open to proof in any conventional sense" (p. 108). It follows from this argument that, while research should make explicit the paradigmatic assumptions upon which it is based, and these assumptions may not be universally shared, there is no sound basis for criticizing research only for its assumptions.

The point is that all human knowledge, all scientific research, follows a set of procedures that must begin with a group of assumptions, a set of beliefs, a paradigm. And yet, qualitative research studies, indeed whole fields of qualitative research, are frequently criticized for their methodology without any consideration of the paradigm within which they fall. It has been argued that all scientific research fits into one of three basic paradigms, i.e. there is an unavoidable tension between the paradigms of: positivism, critical theory, and contructionism. These cannot be simply defined, they cover a variety of positions, and there are further positions that attempt to integrate them. Guba & Lincoln (1994) do include a fourth paradigm: post-positivism, and Valle (1998), Heron (1998) and Braud & Anderson (1998) clearly propose a transpersonal paradigm.

Another feature of this model is that while paradigms do promote different strategies and methods of research, these are by no means exclusive to any particular paradigmatic approach. The model also clarifies the need to distinguish method (data collection) from analysis (of data).

(6) STRATEGIES OF RESEARCH

Another important distinction that arises from this model is the recognition of the nature of research strategy as opposed to methods of data collection. Strategies are often overlooked both in the reporting of research and in the teaching of students. Strategies represent options and choices for the researcher. They promote but are not in themselves methods for collecting data.

For example, formulating a research question and selecting a research focus, choosing hypothesis testing vs. data driven approaches, requiring a contextual analysis and thick description, all are concerned with choosing a strategy of research. Deciding how is the phenomenon to be sampled, giving emphasis to the experiential nature of the area for participants (phenomenological - cf. Moustakas, 1994) and the researchers themselves (heuristic - cf. Moustakas, 1990) may be involved. And further considerations might include: attitudes towards participants (cooperative inquiry - cf. Heron, 1996), the involvement of the researcher (participant inquiry - cf. Reason & Rowan, 1981; Reason, 1994), and, the possibility of including several different approaches to data collection (triangulation - cf. Denzin & Lincoln, 1994).

Strategies of research provide important links between the research paradigm and methods of data collection and analysis. They are not peculiar to the qualitative approach, but have been made more explicit there. A closer attention to strategies could prevent much of the muddled thinking that is around. It is with an attention to strategies that the various paradigms can be regained for psychology.

(7) AN EXAMPLE: TRANSPERSONAL/DISCURSIVE RESEARCH

To illustrate this framework in action, we will consider the field of transpersonal psychology. Over the last few years, and the past year in particular, there have been several exciting publications:- Braud & Anderson (1998) offer five new methods of disciplined inquiry – integral inquiry, intuitive inquiry, organic research, transpersonal-phenomenological inquiry, and, inquiry informed by exceptional human experiences; Valle (1998) has gathered together the research underpinnings of a new paradigm – existential-phenomenological psychology, within which he specifically identifies an emerging transpersonal-phenomenological psychology (Valle, 1995); and Heron (1998) outlines a sacred science that combines research from both co-operative inquiry and lived inquiry. The point here is simply that as psychology matures, and new paradigms emerge, so new strategies, methods and analysis tools will develop. And, if the list is getting a little long, and unmanageable, then what is needed is only a model to organize it.

In addition, issues raised by my own research in the field of counselling and psychotherapy also illustrate the point. These studies range over an examination of "interrupted" narratives in counselling practice (Hiles, 1996), an exploration of intersubjectivity and intrasubjectivity (Hiles, 1997), and a heuristic inquiry into loss, grief and transformation (Hiles, 1999). All of these studies are concerned with a study of meaning, especially as expressed in narrative, in drawings, and other material. My initial approach to analyzing the material was to use discourse analysis techniques.

The use of these discursive techniques revealed problems with the underlying paradigm, i.e. social constructionism, subject positioning, and human subjectivity. I was finding out first-hand that data analysis tools are not neutral. This demonstrated clearly some of the pitfalls that paradigm confusion can engender, and illustrated the real advantages of placing research within a framework that distinguishes between paradigm, strategy, method and analysis.

(8) CONCLUSIONS

This paper argues for the rejection of the simplistic qualitative/quantitative distinction. It problematizes "methods" in the need to distinguish methods of data collection from methods of data analysis. There is a clear need to articulate in the planning, carrying out, reporting and teaching of research the four components of paradigm/strategy/method/analysis. These constitute the chief components of a generalized model of Disciplined Inquiry. This model highlights how we are overlooking the importance of research strategies - especially how they interface between paradigms and methods. From this perspective a stop can be put to the naive criticism of research for its methods. Too often the real issue is a clash of paradigms.

REFERENCES

Banister, P. et al. (1994) Qualitative Methods in Psychology: A research guide. OU Press.

Braud, W. & Anderson, R. (1998) Transpersonal Research Methods for the Social Sciences: Honoring human experience. Sage.

Breakwell, G.M., Hammond, S. & Fife-Schaw, C. (Eds) (1995) Research Methods in Psychology. Sage.

Denzin, N.K. & Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds) (1994) Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage.

Giorgi, A. (1970) Psychology as a Human Science. Harper & Row.

Giorgi, A. (Ed) (1985) Phenomenology and Psychological Research. Duquesne University Press.

Guba, E.G. & Lincoln, Y.S. (1994) Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Chapter 6 in N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds) Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage.

Hayes, N. (ed) (1997) Doing Qualitative Analysis in Psychology. Psychology Press.

Heron, J. (1996) Co-operative Inquiry: Research into the human condition. Sage.

Heron, J. (1998) Sacred Science: Person-centred inquiry into the spiritual and the subtle. PCCS Books.

Hiles, D.R. (1996) "Interrupted" narratives and counselling practice. Paper presented to BAC 2nd Annual Counselling Research Conference, Birmingham, March 1996.

Hiles, D.R. (1997) Intersubjectivity and the Healing Dialogue in Counselling Practice. Paper presented to BAC 3rd Annual Counselling Research Conference, Birmingham, June 1997.

Hiles, D.R. (1999) Loss, Grief and Transformation: A heuristic inquiry. Paper presented to 18th International Human Science Conference, Sheffield, July 26 -29, 1999.

Janesick, V.J. (1994) The dance of qualitative research design: Metaphor, methodolatry and meaning. Chapter 12 in N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds) Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage.

Lally, J. (1998) Letters to the editor. The Psychologist, 12, 579-580.

Morgan, M.J. (1998) Qualitative research - science or pseudo-science? The Psychologist, 11, 481-483; (& the Postscript, p. 488).

Moustakas, C. (1990) Heuristic Research: Design, methodology and applications. Sage.

Moustakas, C. (1994) Phenomenological Research Methods. Sage.

Polkinghorne, D.E. (1982) What makes research humanistic? Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 22, 47-54.

Polkinghorne, D.E. (1983) Methodology for the Human Sciences: Systems of inquiry. SUNY.

Reason, P. (Ed) (1988) Human Inquiry in Action. Sage.

Reason, P. (Ed) (1994) Participation in Human Inquiry. Sage.

Reason, P. & Rowan J. (Eds) (1981) Human Inquiry: A sourcebook of new paradigm research. Wiley.

Richardson, J.T.E. (Ed) (1996) Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for Psychology and the Social Sciences. BPS Books.

Robson, C. (1993) Real World Research: A resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. Blackwell.

Smith, J., Harré, R. & Van Langenhove, L. (1995a) Rethinking Psychology. Sage.

Smith, J., Harré, R. & Van Langenhove, L. (1995b) Rethinking Methods in Psychology. Sage.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. (2nd Ed. ). Sage.

Valle, R. (1995)Towards a transpersonal-phenomenological psychology: On transcendent awareness, passion, and peace of mind. J. East-West Psychology, 1, 3- 15.

Valle, R. (1998) (Ed) Phenomenological Inquiry in Psychology: Existential and Transpersonal dimensions. Plenum.